|

As summers always do, this one sped by. On the positive side, I had more of a chance to rest and recuperate than last summer because of all the meetings and planning we had. In fact, I made a wise decision this summer and backed out of a few committees I thought I would work with on different projects, and I am so glad I did so. More than any other year, I needed to forget about school for a while.

In our house, lots has been happening, making it a busy summer in other ways. Helping 2 of my 3 kids prepare to leave home (one for a Coloradan adventure, the other for college) has been very bittersweet for me. Of course I want my kids to fly and to flourish, be happy and independent, have adventures and experience life. At the same time, we are a close-knit family, and I have to admit that my heart hurt saying goodbye to them. We still have one amazing kid at home who will get so much attention, she won't know where to escape to! We've also had a trying time as a family as my dad suffers from old and new health challenges. We are rallying together to support him and each other, and trying to stay positive while managing our anxiety and stress. At the same time, I'm trying to adjust to a new school year, and teaching graduate students, and my PhD program. "One day at a time" is becoming my new mantra. I remember thinking in June, maybe we can go back without masks? But in my district, we are masked again, and I find myself grateful for that as I read and hear about other districts that are leaving masking up to individuals and families while kids and teachers continue to get sick. Teaching English learners with a mask on definitely is challenging because my students can't see my mouth and hear my words muffled, but I would much rather that than compromise the safety of anyone in my school. And with the ever-evolving new strains of COVID, things seem more unsure than ever. As far as COVID learning loss goes, I think that more than the actual learning, a lot of the loss occurred in other areas. Students are learning to be together again in class, to work together in groups, to socialize at lunch, to walk down hallways, to use paper and pencil, and be fully engaged in class because their teachers can see their faces and whole bodies now. I heard somewhere that rather than "learning loss", it was more of a "learning slowdown", and that makes a lot more sense to me. Any day they were online with their teachers and somewhat engaged was a day of learning. Did they forget some information? Or not make as much progress as if they were in the school building? Maybe. But I think we have to give our students more credit, at the same time as we help those who need an extra boost to get them back in the flow. This year, I have two students who are brand new to this country from vastly different places: one from a family of professors from a central European country who are here visiting or doing research, and one who was born, grew up, and was educated in a large refugee camp in a southeastern African country. I don't speak either of their languages at all, so I will have to rely on a lot of gestures, Google translate, pictures, and videos. Two students who are from Central America have been here 2 years but at least one is still in what is called the "silent period". And three students have been here for 3 or so years but still tested at a beginner level in ELL. There is a broad range of educational backgrounds and English levels in my class, and it will be interesting to see how it evolves. Unfortunately, I don't have a student teacher this year, but in at least one class I have an amazing para to help with the diversity of levels and learning styles. In my ELL advanced language classes, I also have diverse groups in terms of home languages, personalities, and areas they need to work on in their "school English." Here is wishing all my fellow educators a positive start to the new year. Take care of yourselves, too, because we have been known to overdo it, caring for and teaching our students.

2 Comments

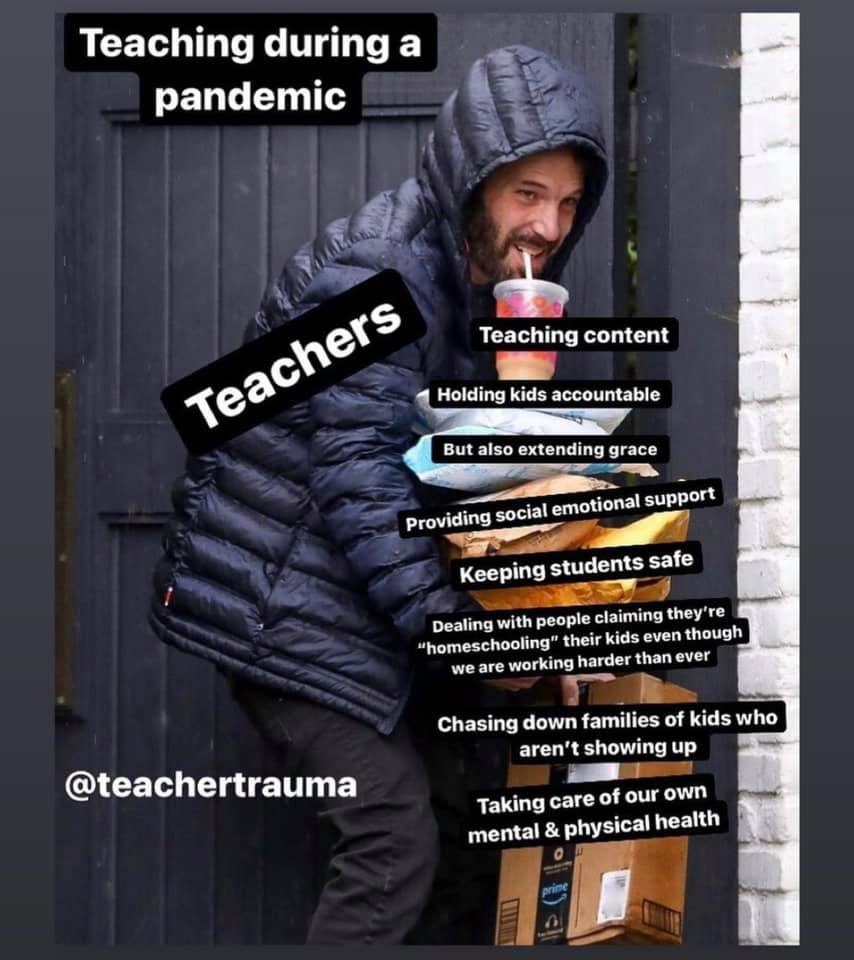

On the longest day of the year, I'm counting the days of the longest school year in history. I have written about how well my students have done this year, and it's true - they have. They have been amazingly resilient, they've grown, they've learned, they've adapted, and they've kept me going. At the same time, I know we are all reaching our limits. The monotony and chaos of teaching remotely and navigating an in person group and a remote group are starting to get to me; the students are definitely getting antsy as well.

Teaching this year has confirmed a lot of things I already knew about teaching. For example, a daily routine is just as important online as it is in person. A daily warm-up helps settle the students in and gives my student teacher and me a chance to gauge how the students are that day, and get ourselves ready for the lesson. Using Google classroom where you can see kids while they work on an assignment is really helpful, and I think it helped students improve their writing maybe even more than in the physical classroom. And, a good game of Kahoot or something else is always a good way to break up class and let the kids have some fun. And, teaching remotely through a pandemic has taught me a lot as well. I've learned that I can adapt a lot of things for online learning, but not all. I learned that putting kids into breakout rooms without an adult present doesn't usually go that well, at least not for middle schoolers. Not having a physical globe or map, we had to devise different ways to teach geography, and that wasn't always easy. I learned that, not being able to move around as much as in the classroom, we all needed a stretch break every day. And most importantly, I learned that you can make warm, strong connections with students even in a virtual format. However....I'm ready for it to end. Ready for summer, for time away from computers, sitting in the sun, without a schedule. I'm ready for a mental break. I'm ready to ease back into "normal" post-COVID life, slowly. Finally, I'm ready to reset at the end of the summer, and start the year fresh - in person, in my classroom, maybe still masked, but there, to share the daily ups and downs of teaching with my colleagues, and to create community with my new students. My friend and fellow educator Sharri Conklin recently posted this on Facebook and I invited her to post it here as a guest blogger.

One year ago, I was going to school each day, worry growing as the news updated us each day with what was coming. One year ago this Friday, our school sent us home. I held it together all day to support my students, but the pit in my stomach knew this was different than anything we had ever experienced before. I have held my students through the death of a beloved staff member, 9/11, school shootings and the daily crises that come with living. This felt different. This felt heavy in a way I had never experienced. As I walked my students to the buses, carrying everything we could think to send home, I began to lose it. I smiled and waved to them as they drove off. When I turned around to head back in the building, I couldn’t hold it in anymore. I went into a room and couldn’t stop crying. Since then, I, along with my colleagues, have learned how to teach through the computer. We took everything we knew about how to teach and adapted it, with no training, to engage students, to keep learning moving forward and to hold social emotional lives during a global pandemic in our hands. Each time we needed to, we recreated what we do to adapt to this new situation, all while trying to run our own households, keep ourselves and our families safe and healthy and moving forward. We bought monitors and computers and upgraded our WIFI and watched videos on how to take everything we did in person and make it accessible through the computer. We connected with families to make sure they were fed and had access to technology and WIFI. We taught students and families how to access learning without being in person with them to do so. Some of our colleagues have since returned to their in person classrooms, some have stayed remote and some have done a combination. Some of us have been heralded, some of us vilified and all of us have felt a combination of all those feelings for ourselves at one time or another. Good teaching is adapting. It’s what we do. Adapt to the unique learners, the new standards, the new methods, the new rules that change overnight. And we do this because we love our kids and our community. We really don’t ask for a lot. We spend our own money, spend our own time and lose our own sleep over our jobs. We are, at once, not important enough because families can teach their own kids at home without us and so important that families can’t function if their children aren’t in school. We get it. Life is messy and hard and changes on a dime. We get it. It’s what happens in a day, in an instant, in schools all the time when there’s a shooting or a death or a job loss of a parent or a deportation or a jailing or DCF report of abuse or systemic racism or a global pandemic. It’s emotional and it’s draining. We are sorry this school year has been unlike any other. We are anguished that students and families are suffering. But it’s not all on us. We are fighting to keep ourselves and our families safe and sane and healthy, too. We are sorry we can’t ignore everything in our own lives to come in person to help your family who is also suffering. Just like you, we have personal experiences and unique family situations that force us to make hard decisions. But none of us have not been working. None of us are lazy. None of us are looking for the easy way out. We are all just trying to make it through this global pandemic the best we can. So as things in our communities change in the next months as the state forces all schools to open buildings no matter what to any families who want their children to come back, please remember we are all doing the best we can. We will remember you are, too. Sharri Conklin has been an educator for more than 25 years. She is currently a 5th grade teacher in Amherst, MA.  We've passed the one year mark of the first COVID case in Massachusetts, and it's been more than a year since the first cases were reported in the U.S. March 13 will make a year that I haven't taught inside my school building. We left school that day thinking we'd be gone for 2 weeks, but by the beginning of the second week, I had a feeling it would be much longer. I've been teaching remotely for a year. Teaching is an exhausting profession in normal times, but I find myself tired in a way I didn't know before. It's not the same tired as when I was the new mom of 3 kids under the age of 3 - a physically exhausting kind of tired. It's different from the tired I felt of working full time and getting my Master's, when my kids were 7, 5 and 4. This is different. I've read a lot about stress and how it manifests, and the stress people are feeling during the pandemic, and I recognize it. The foggy-brain, the lack of motivation, the sheer exhaustion. I'm usually a motivated, organized person who structures all of her time, so when I feel this lack of energy and focus, I have a hard time understanding what's happening. I am learning to have compassion for myself and be more forgiving of others, too. Teaching remotely, or online, should be easier, or so people think. The fact is that I put so much energy and thought into every single lesson that it leaves me spent at the end of each day. Teaching online leaves no room for winging it. Once I have my students with me, I need to keep them with me. I want to engage them, give them work, hold them to high expectations - but not too high, because I don't want them to check out. I have a student teacher, which is amazing, because she's great and there are two of us to put our heads together to plan and create activities. And yet, I am still exhausted in this new way I hadn't known before. So, no - teaching online is not easier just because I'm home. Sure, I can take care of some household tasks, enjoy a quiet cup of tea for a few minutes, or pet my dogs, and all of that makes teaching remotely feel more humane - but not easier. I know I'm luckier than many teachers: my kids are in their late teens and don't need much supervision; I like my family and we get along well; we each have a dedicated space from which to "do school" (though mine is my bedroom, I don't have to share it with anyone); my union is strong and supportive of all teachers; I was granted the right to stay remote because of health (unlike in some districts, mine has been great about this); my kids' mental health is pretty intact; I'm in a two parent household and I have job security. I know people are struggling. People all over the country are going through an extremely challenging time. The consequences of the pandemic are far-reaching and staggeringly tragic. But - teachers are being blamed for things that are beyond our control. We are being blamed for being fearful, not listening to science, only caring about ourselves. We are being blamed for hiding behind our unions, and they are being blamed for fear-mongering. We are being blamed for the state of the mental health of students, for the inequities that are finally coming to light but which we were seeing every day in our schools, and for kids falling behind this year. Yet, teachers in my state are not eligible to be vaccinated yet, schools have windows that don't work or that you wouldn't want to open when it's 12 degrees out like today, and not all of our schools are physically ready to reopen. The pandemic has only made things that I knew much more clear to me. Injustices and inequities in our schools are urgent matters that needed our attention before, and need it even more now. Standardized tests were inequitable before, and will be even more so this year if schools administer them, like Governor Baker in MA wants to do. My union is here to support me; I AM the union. My fellow teachers and I are a community. My students know I care for them and they matter to me. Teacher voices need to be heard, amplified, and included in conversations, especially about policy and funding. And on a personal level, my well-being and health come first. Self-care has a new meaning for me. I still love my profession. And - my family is everything. Dear Maestrateacher,

Our relationship began 6 years ago, when I wanted a way to celebrate my 20th year of teaching. Like most relationships, we started out strong and consistent. I wrote you every day for a month! Hard to believe that, looking back. Gradually, as my kids got older and responsibilities piled on, my posts went weekly, then biweekly, then, sadly, monthly. Now, I have abandoned you since October 2020! We're in a new year, and I haven't even given you a glance. But, let me explain myself. Maestrateacher, a lot has happened! You already know about this distance teaching thing because of the COVID-19 pandemic. Well, guess what? We are STILL in a raging pandemic, we've had at least 2 big surges since Thanksgiving, and daily cases are at an all-time high. Most of the world is experiencing a similar situation (except maybe New Zealand, and parts of the African continent). Thankfully, there are now 2 vaccines that have been approved, and the first group of people is getting it (my sister, as a healthcare worker, was immunized yesterday). But in the meantime, people keep doing dumb ass things and spreading the coronavirus. A new year started since we spoke last, and boy did it start with a bang. Yesterday, January 6, 2021, thousands of Trump supporters stormed and attacked the Capitol building in DC, infiltrating it, breaking windows, occupying offices, and taking selfies with statues of Reagan and Nixon. I'm being completely serious. This HAPPENED. We were at home, because for the first time in my teaching career, I had the day officially off for Three Kings Day. Unfortunately, after getting an urgent text from a friend in a group chat - Turn on the news! - we did not feel like celebrating anymore. Today, my students stepped up with great questions, concerns, and thoughts about what had happened. One brought up the fact that in last summer's BLM protests, the police reacted VERY differently, with rubber bullets and tear gas, and yesterday, we observed police officers politely escorting the infiltrators down the Capitol steps. No one can try to claim this was a calm protest, as many of the BLM protests were. People in this crowd were scaling walls! With weapons! They brought the Confederate flag INTO the building! As my daughter said, that is actually very un-American. So, Maestrateacher, how do we keep our heads up in these crazy times? Like I've told you before, my students are resilient and amazing, I love them, and they inspire me every day. They have been doing great despite all the challenges. They keep me going. My own kids also keep me going, I see them, heads down, doing their work, trying their hardest, and they make me want to do better for my students. Family is everything. My parents are also a constant source of inspiration and motivation; you never stop wanting to make them proud, even at 51. And, my dogs. I am sure that thousands of other dogs, like mine, have begrudgingly become therapy dogs. Maestrateacher - this is NOT a breakup letter. I want to come back to you and make this work. I did consider leaving you, I'm not going to lie; you were becoming a burden. Our yearly subscription payment was due in October and I seriously thought about making that a clean break from you. Then, I realized that I still love you. You make me continue writing, which helps me process everything happening. Maybe I just needed a break. I can't promise to write every week, but I can be here more often. Will you take me back?  "This is going so great!" said one of my ELL students last week. Surprised by her comment, I responded, "That's awesome! I'm so happy to hear this. Can you tell me why?" The student, who arrived almost 2 years ago after having grown up on a refugee camp, told me that at first, distance learning was hard because of all the technology, but then, she got used to it, and it was going great. A few other students nodded in agreement with her, and said "yeah, me too." ELL students tend to be a more vulnerable group, and as students at the beginning stages of learning English, my students have a myriad of challenges and traumatic events in their lives. Thus, in my town, the decision was made to bring beginner ELLs back in Phase 1 of our plan (along with some special education groups). Originally starting at the beginning of October, phase 1 had to be postponed because of a surge of Coronavirus cases; now, the cases have stabilized, and phase 1 will begin later this week. My students' comments are not reflective of the typical narrative we have been seeing and hearing on the news. Yet, here they were, a month into distance learning, with unlikely sunny dispositions. The particular student who told me it was going great lives in an apartment with one parent, 2 baby nephews, and 7 or 8 siblings who are in school too. Another student is in class with me in the same room as her sibling, a high school student, and I can hear everything my high school ELL colleagues say as they teach. As my students smiled through their cameras, I felt lucky and relieved that it seemed to be going well for them. I wondered how much of the success we were having together was due to the fact that I had some of the students last year, and only a few were new to me. I had been able to be in the physical classroom with some of them for a good 7 months, and we had built our small community. They were showing up every day, on time, participating via the chat or by commenting, and doing and turning in their work. My other classes have been a mixed bag: some very successful days, some mediocre days, some days where I just want to cry after class. But, the resilience in my beginner ELL group has shown me that we can indeed be successful at distance learning. Even when the WIFI goes down or is overloaded, even when I ask for volunteers and the wait time silence is deafening, my spirits are kept up because I know my students are there to keep me going. I learn to interact with them onscreen a little better each day. They make me laugh and smile, and they bring me joy. Sometimes, when I feel frustrated and find myself staring at a screen of avatars, photos, or names instead of faces, I think of one of my Zumba teachers (I have many! They are amazing! They helped me through the pandemic in the spring!). Stephanie, also a public school teacher, started doing Zumba online soon after everything closed down. Stephanie doesn't worry if she doesn't see our faces onscreen, and frankly, not many people in the class want to have their video on while doing crazy Zumba moves. Stephanie cheers us on from her side, pointing at us and giving thumbs-up signs, encouraging us to enjoy ourselves. She always begins and ends class with a positive message, which lets us know that she is excited to be there and appreciates us. She is consistently smiley and super-energetic, and her positivity is catchy. By the end of class, I always feel happier and am smiling, too. I try to channel Stephanie and bring my best to class, too. Certainly, remote teaching is not the same as being in the same physical room together, but it is going much better than I anticipated. How's it going for you? In my years of teaching, I never thought I would start a school year in this way - teaching remote classes, attending meeting by video only, planning with colleagues without being in the same room as them. I'm sure that most teachers feel as bewildered as I do right now - as well as anxious, terrified, stressed, and totally exhausted even before classes have actually begun.

Today, the eve of the start of classes in my district, I am feeling all of the above, as well as feeling totally unprepared. We were so lucky in my district to have 2 weeks to prepare before classes. Some of that time was taken up by taking an teaching online "boot camp". We also had many meetings the first week. The second week, we finally had more time to prepare our own classes. I revised the course maps of some classes, set up a Google site and my Google Classrooms. Finished with all of that, I tried to sit down and actually plan lessons for at least the first two weeks of class. Every time I tried to work on this, I felt totally stuck. I'm usually able to crank out lessons easily (I would hope, with so many years of teaching behind me), but not this time. I realized the issue was not only me, but the fact that there are so many unknowns still, holding me back from being able to prepare. So on the day before I start teaching, here I am blogging instead. A lot of blogs and articles have been published over the summer describing teachers' anxieties and stress, and worried about COVID-19 and going back to school. Of course, there are many many sad aspects of not seeing our students in person, for those of us who are teaching remotely. Teaching in person gives you a different energy than teaching online. Body language and facial expressions, especially in teaching ELL, are everything. There is no comparison to working with colleagues in person rather than on video. And, of course, what is a middle school without its building, hallways, cafeteria, and screaming, running, twitching middle school students? There are a few advantages to teaching from home. The obvious one is not having to travel anywhere, though I really can't complain about my normal 8 minute commute. I enjoyed seeing our yearly convocation on YouTube this morning, rather than seeing it in person in a humid, airless auditorium. And, instead of sitting for 2 hours to watch the death-by-PowerPoint mandatory slides every year, this year we were able to view them on our own and sign off that we completed them - this should always be done like this! What a waste of time it usually is. Our secondary schools' classes have been cut in half in quantity and will be taught in blocks so that kids don't have too many transitions. Finally, rethinking how we are addressing racism in our district has led to many teachers attending workshops, forming book groups, and entirely revamping their curriculum to include more voices of color. Challenges made us think carefully about how we have always done things - just because they have been always done this way doesn't mean it's right or good for kids or teachers. Hopefully some of these positive changes will stick after COVID-19 is a distant threat. As I come to the end of this blog, I wish all teachers everywhere strength and endurance, and most of all, good health, this year. One consolation for me has been that teachers all over the world are facing the same challenges and hardships this year. I guess I can't avoid it anymore - it really is time to go prepare now! I used to joke with people about teachers working from home: "I wish I could work from home", I would say, laughing at what a ridiculous notion that was - a teacher, working from home? Ha! Then COVID-19 happened. Who knew that teachers would be trying out all kinds of engaging new tricks, expanding their knowledge of tech tools and attending online PD about distance teaching? I wasn't surprised when we closed, and I soon realized that it would probably be for the rest of the school year. Recently, I went into school (as many teachers are doing) at a pre-designated 2.5 hour slot to clean up my room for the summer. Being in a quiet, dark middle school with no signs of life was a surreal experience. And, packing up my room for the summer in late May was, as well. My teacher brain got mixed signals from this - only May and my room is ready for summer, yet we still have a month of distance teaching left? I didn't know what to leave and what to take home, since we don't even know what the fall will look like yet. There is nothing quite like distance teaching ELLs to make one feel like a failure at teaching. Beginner English Learners are often timid about speaking English already; put them in from of a camera and microphone for a Google Meet and they revert to the shy kids on they were on the first day of school. Often, they don't want to show their faces on camera, some preferring to write in the chat instead. Using Spanish and Portuguese to communicate with some of them doesn't really work while they are all in a Meet together. If they show up, that is. Many kids are, naturally, sleeping really late (12, 1, 2 PM) and miss the Google Meets. I can't reach them or engage them in the same way, even with multiple emails and texts and phone calls home, please for help to their interpreters, and messages on Google Classroom or via email directly to them. It is definitely frustrating. I have had luck with one class - my class of 7th grade academic language students, which is tiny. 3 out of 4 have been showing up weekly to check in and share their writing from a writing prompt slide show I made for them based on prompts from the New York Times Learning section. Each week's prompt has a model prompt by me. Then they respond to the prompts in writing and we share when we meet. One prompt was to recount your life, currently, in numbers. One of my students gave me permission to share her answer, which I thought was profound: "Your life in numbers. What does your life right now look like if you used numbers to describe it?" 12 - the number of hours I’m bored each day. 6 - the number of hours of sleep I’m getting each day. 4 - the number of hours I spend on homework each day. 3 - the number of Netflix shows I am currently bingeing. 2- the number of days I’ve been outside in the past week. 1- the number of hours I spend on my phone each day. 0 - the amount of times I’ve seen and talked to my friends outside a screen. (by Ivanilse Varela Vaz, with her permission) I miss my students every day. It feels wrong that I cannot be with them to break down the events of the last 2 weeks, the savage murder of George Floyd and the worldwide protests, as I would be doing if we were face to face, physically in the same room. I imagine we would have watched videos to help their understanding, and read articles or slide shows to explain the contest of Black people in the United states. We could have taken small actions to create awareness. Maybe our school would have had a sit in or a walk out. Now, we are talking about possibilities for the fall, and frankly it is not looking great. School will not look the same. All I can hope is that my students and I can make the best of it, build our relationship in new and creative ways, and help each other get through these dark times. And, I hope that the last sentence in my student's writing: "0- the amount of times I've seen and talked to my friends outside a screen", is less true. And I REALLY hope that 2020 gets better from here on out. At the beginning of the pandemic, teachers received hundreds of emails with online resources. We were overwhelmed with PDs, free online platforms, tips, and more. We soon realized it was more challenging than any of us thought it would be.

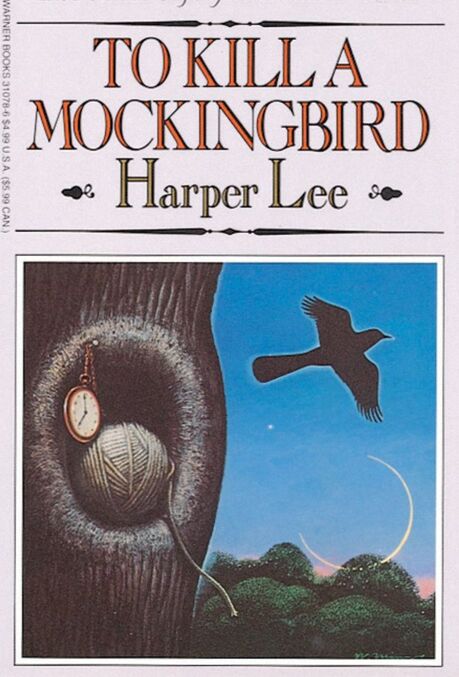

Distance teaching is not ideal for many students, and is frustrating for many teachers. Some teachers (like me) are finding it hard to engage their students, and it is difficult to gauge how much students are involved and doing some school work. Nevertheless, some creative projects are happening - teachers are adaptive and resilient. When I saw this collaborative poem by students on one of the 7th grade teams at my school, I was impressed by what I read. The teachers, Heather Sullivan-Flynn and Patrick Hunter, gave me permission to publish it here. I asked the teachers about their process in guiding students during this unit. The teachers explained that students read Kwame Alexander's crowd-sourced poem "Social Distance" so they could see how it worked. Previously, they had responded to a prompt for individual poems where they had to look in nature or their homes for something that stood out or seemed like it didn't belong, hence the theme "belonging" for their final poem. The teachers created a slide show of images to show belonging, such as multicolored, clasped hands, and a photo of the team of 130 students. Then, the students were asked to write 1-2 lines about belonging. They were encouraged to use poetic language, such as metaphors, to express their feelings of belonging. The final result, after some editing by the teachers, is this awesome collaborative poem! Read below: Belonging: a collaborative poem written by Team Midnight students Belonging- a feeling of togetherness, being a part in this world, where you talk and feel heard different skin- different face- different religion- but it doesn't matter because we are all the same A herd of mustangs a mob of black, tan, brown, white galloping in a sense of togetherness A collection of ocean rocks refusing the ocean’s force never have to hide secrets kept frozen under goosebumps and stale smiles. Knowing this is the place for you like knowing the answer on a test we are worthy of kindness it is working together that makes us feel like we belong A warmth like bat’s wings wrap around to feel comfort and peace- Belonging feels like connecting, heart to heart We all should be treated equally even though we may disperse, we won’t cascade apart our hands are locked holding you up, and keeping you safe we are in this together Hands, reaching out to hold one another, the colors of fluffy pillows, golden sunsets, and deep warm browns- Like the stalks of a new plant- Like birds chirping in the summer- as the dandelions sway holding each other’s hands to create one family. Separate we are just people, but together we are a family- we come together and our community grows searching warm gazes your heart beats with the knowledge that you are loved- that you belong here: a loving community where you can be you As humans we want to be in the circle to stay in the circle to live in the circle everyone, together, being human and having fun- we are all in this together we will all have each other's back and we will each be there for someone You're not alone- we are all here in this circle together. It’s a good feeling to know that you fit in to feel that you belong. Everyone in our community belongs- no matter our differences we get along Everyone has different backgrounds, but everyone has feelings. Though sometimes things are rough and looking very tough the strength and love of a community holds us together- you can be different but still belong where one becomes many and many make a difference Together It's better It feels like sunlit gold Like a sweet smelling flower Always together with bees Together is always better Similarities are only found with differences Peace is a miracle, working together is another But finding a place to belong is full of mixed emotions I belong when the people around me accept who I am Belonging feels like a piece of an image fitting with the other pieces another piece to a greater puzzle that soft, warm, delicate feeling of knowing you are loved. We are all together drifting through the current all wanting to get to the same place all doing it together and though we don’t know We will all drift past each other not even noticing that we all were once in the same boat rowing in unison to the beat of the waves. It’s easy to think of belonging when you already have help Everyone plays a role in society to help everyone belong everyone is different and deserves to be included Belonging isn’t always easy Belonging is warmth Belonging is comfort and relief but most importantly Belonging is safe Together we all stand, included- you are meant to be here- To know belonging is to know there is a place for you like a petal on a flower, you belong- You are meant to belong. Heather Sullivan-Flynn has been teaching middle school English for 22 years, the last 18 of them at Amherst Regional Middle School. She lives in western Massachusetts with her family where she writes fiction and drinks tea. Patrick Hunter teaches English and Social Studies at Amherst Middle School. Stepping Away from the Safety Net in Teaching To Kill a Mockingbird; a Guest Blog by Emma Canales5/10/2020 Dr.Keisha Green is Assistant Professor in the College of Education at UMass, Amherst, whose scholarly work revolves around English Education, critical literacy, critical pedagogy, and youth literacies. In Dr.Green's class, African-American Literacies and Education, students are asked to write a "dialectical rewrite" of an issue that "keeps them up at night."

Emma Canales, one of Dr.Green's students, decided to write about To Kill a Mockingbird. She explained her rationale for writing about this book: "I teach 8th grade ELA in [a local city with schools that have a high population of African-American and Latino students]. My students are predominantly of color and I realized after taking Dr. Green's class that education is vastly out of touch with the lives of these students. I was teaching To Kill a Mockingbird and happened across the scene that I examined in my writing. It was really disheartening to hear my students agree that Calpurnia shouldn't be code switching and that if she "knows how to talk right then she needs to talk right" implying that Black English is "wrong." The rich and historical heritage of Black English is being ripped away from our students and I realized that the curriculum needs to be recentered around them." Below, I share her dialectical rewrite with you. I'm interested to hear thoughts from people who also teach TKM, or have taught it in the past! My urban English Language Arts class is currently delving into the high school classic To Kill a Mockingbird by Harper Lee. This is my third year teaching the novel and my first year realizing that, as a white teacher in a predominantly Latinx and Black classroom environment, I need to recenter the curriculum around my students and what is relevant to their lives and away from has always been a white supremacist agenda. Harper Lee was a white Southern woman, and although she certainly did encounter brutal racism and violence, she did so from the safety of her own whiteness, and was merely a spectator. To Kill a Mockingbird is often used as either a launching pad in the classroom to discuss race and equity, in most likely a watered down context so that it can be discussed “safely”, because many teachers and school administrators fear such heavily charged discourses. Educators need to step away from their safety net, which may be their pre-designed curriculum or the curriculum that they’ve been following unwaveringly for years, and ask themselves: who are they centering? What books are they reading and discussing in the classroom? Who wrote the books and under what circumstances? Finally, if teachers cannot deviate away from what books they are being required to teach, they need to examine their practice to ensure that their methods are not only inclusive of Black and Brown students, but that these students are able to participate fully and in a way where their voice is valued. Why is there such a reluctance to include literature written by authors that students can actually identify with which demonstrates topics and ideas that students can passionately discuss? H. Samy Alim and John Baugh (2007) phrase it perfectly when they state, in Talkin Black Talk: Language, Education, and Social Change, “...the American public education system [is out] of touch with both contemporary reality and the historical reality of Black Americans” (p. 19). The majority of teachers are white and it would make sense that the public education system is “out of touch” because white teachers are designing and creating curriculum centered around the white experience. This is their comfort zone and their default approach. There needs to be a push, and it may prove to be difficult and feel uncomfortable, for teachers to get in touch with what can be relevant in the lives of students that may not look like them. For example, To Kill a Mockingbird is written from the perspective of Scout, a white child. It is easy to teach from this character’s perspective, but in doing that the teacher is once again furthering and valuing the white perspective. More attention and character examination must be paid to the Black characters in the novel, but this must be done carefully. A teacher may choose to focus on the character of Calpurnia, but if this focus is done around the fact that she has literally lived to serve the white Finch family, then once again this furthers the notion that the Black experience is only worth mentioning when it is tied to white lives. An educator should try recentering this character around key questions such as: even though Calpurnia is “employed” by the Finch family, given the historical context, did she have much of a choice? What were Calpurnia’s options in the 1930’s in Alabama? These questions could be discussed in a larger lesson around the political, cultural, and economic context of the South in the era of the Great Depression and what impact these factors would have had on Calpurnia. There is a scene in To Kill a Mockingbird that shows the slow and insidious creep of oppression working its way into the curriculum and mind of the youth in urban schools in particular. In this scene, Calpurnia takes the Finch kids to her church which serves the African American population of their town. When they arrive, Scout and Jem observe Calpurnia speaking differently to “her people” (code switching) than how she speaks to the children at home. Near the end of this scene the following exchange takes place: “Why yes sir, Mister Jem.” Calpurnia timidly put her fingers to her mouth. “They were the only books I had. Your grandaddy said Mr. Blackstone wrote fine English—” “That’s why you don’t talk like the rest of ‘em,” said Jem. “The rest of who?” “Rest of the colored folks. Cal, but you talked like they did in church…” That Calpurnia led a modest double life never dawned on me. The idea that she had a separate existence outside our household was a novel one, to say nothing of her having command of two languages. “Cal,” I asked, “why do you talk n-talk to the—to your folks when you know it’s not right?” “Well, in the first place I’m black—” “That doesn’t mean you hafta talk that way when you know better,” said Jem. Calpurnia tilted her hat and scratched her head, then pressed her hat down carefully over her ears. “It’s right hard to say,” she said. “Suppose you and Scout talked colored-folks’ talk at home it’d be out of place, wouldn’t it? Now what if I talked white-folks’ talk at church, and with my neighbors? They’d think I was puttin‘ on airs to beat Moses.” “But Cal, you know better,” I said. “It’s not necessary to tell all you know. It’s not ladylike—in the second place, folks don’t like to have somebody around knowin‘ more than they do. It aggravates ’em. You’re not gonna change any of them by talkin‘ right, they’ve got to want to learn themselves, and when they don’t want to learn there’s nothing you can do but keep your mouth shut or talk their language.” This scene has so much to unpack for educators. It has the potential to be a great discussion topic and learning experience for all. It also has the potential to further the implications that speakers of Black Speech are unable to speak Standard English and instead have to speak in a way that, as Scout put it, is “not right.” Calpurnia doesn’t correct Scout, but instead perpetuates this oppressive narrative by agreeing that she has to speak their language despite its apparent incorrectness. Remember, Calpurnia is a Black character being written by a white woman. Of course she doesn’t correct Scout...the author is showing that Scout is correct in her thinking that the English Calpurnia speaks is incorrect. While Harper Lee does use the word “language” multiple times to describe Calpurnia speaking Black English, she also includes the n-word to describe it, thus delegitimizing it. Harper Lee also has Calpurnia admiring the “fine English” of Blackstone’s Commentaries, which suggests that she appreciates Standard English more than she does her own English and that she only speaks Black English because nobody in her Black community wants to ‘learn” how to speak correctly...in other words, she chooses to only speak Black English to stoop to their assumed lower level of intelligence. I can’t imagine how students reading this scene in an urban classroom feel. By the time my students arrive in my 8th grade classroom, I can guarantee they’ve already felt the unrelenting oppression of educators trying to force Standard English upon them because public education has deemed that Standard English is correct and what students of colors speak isn’t. To make things worse, we open up a book that has been a classroom staple for decades, only to have a white author try to speak as Calpurnia, a Black character, and read that Black English is the language spoken by those who don’t want to learn how to speak “right.” While I was checking for understanding around this scene, an African-American student raised their hand and told me that Scout and Jem were surprised because they thought that Calpurnia was “smarter than that.” I asked what the student meant and they responded with something along the lines of, if Calpurnia were smarter she would speak “properly” all of the time and not just when she chooses, and that she is “fake” for switching how she talks depending on who she is talking to. My student’s response also shows that code switching or having, as Harper Lee put it, a “command of two languages” isn’t valued as an extremely useful ability, or even acknowledged as a necessity in the lives of many students. An educator that doesn’t have a goal of recentering curriculum around Black students may very easily accept the scene at face value and lead a discussion around the improperness of Calpurnia’s speech. This projects the message to the Black students in the room that the way they speak is wrong. The way their family speaks is wrong. When everything about you is made out to be wrong and harshly criticized, then what is the use of participating in class? In speaking up? Black students begin to internalize this racism, lose faith in the educational system, and eventually lose confidence in themselves (Baker-Bell, 2019). It is our responsibility as educators to inform ourselves in ways that classroom cultures and curriculum continue to oppress Black students and their voices while furthering white supremacist agendas. It is then our responsibility to put the hard work in by taking a critical look at our curriculum and our methodologies and pushing through the discomfort of discovering our missteps. We need to correct these missteps. We need to sit with the discomfort and push back against the oppression that we are being asked to replicate. We need to reframe curriculum, reframe novels, and reframe discussions to make space for Black voices to be heard and valued, not squashed and dismissed for being “improper” and thus invalid. References April Baker-Bell (2019): Dismantling anti-black linguistic racism in English language arts classrooms: Toward an anti-racist black language pedagogy, Theory Into Practice, Alim, H. S., & Baugh, J. (2007). Talkin black talk: Language, education, and social change. New York: Teachers College Press. Emma Canales has always called Massachusetts her home and obtained her Bachelor's of Arts degree at the University of Massachusetts Amherst and is attending UMASS for her Master's of Education as well. She is an 8th grade English Language Arts teacher in Springfield, Massachusetts and loves hanging out with and listening to her lively middle school students' thoughts about the world. |

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed